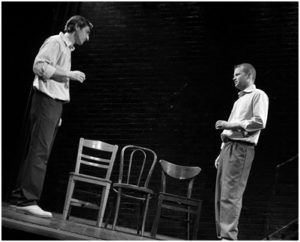

I recently taught a workshop on Dramatic Improvisation for a Comedy Festival focused on Improvisation and Stand-Up comedy for adults. Mine was the first workshop of the day (a Saturday), and I had anticipated a small turnout of people, mostly men, who might resist all but the hilarious and shallow. Why? Because Dramatic Improvisation only works with deep vulnerability and an almost intimate relationship with a scene partner, who may be a stranger. It’s hard to do, and if the commitment to the scene partner is not complete, the scene is unsatisfying. It’s also not necessarily funny (although it can be), and has the potential to be beautiful and raw. Kinda doesn’t fit Saturday Improv Comedy Fest, but that’s what I was asked to teach.

Well, it’s true that people dribbled in and it’s true that they were men with one late exception, BUT they were receptive, worked hard, took direction, and did some poignant, funny, breath-stopping work that was character-driven rather than joke-driven. They took direction and critique and grew in awareness and, yes, intimacy.

I have given this outcome and my own prejudice a great deal of thought in the days since. I typically teach Dramatic Improv and Contact Improv (another deeply personal and wonderful improv form that is movement based) to teenagers, and the hard part is always inching them towards the  letting go of their outer walls, helping them to launch themselves into a moment where they are vulnerable co-stewards of an intimacy of emotion and raw honesty made public.

letting go of their outer walls, helping them to launch themselves into a moment where they are vulnerable co-stewards of an intimacy of emotion and raw honesty made public.

To be clear, I don’t mean “intimacy” in the sense of sexuality or sex scenes. In Contact Improv, the intimacy is both physical and emotional; students’ bodies stay in contact as they discover and apply what are, in essence, planetary and geographical physics. They must learn to not be self-supporting, but rather co-steward as they move through poses hunting for balance, center-point, centripetal force of the unit which invariably puts them as individuals in a place where they would fall if they let go or tried to use brute force instead of trust, vulnerability, and connectivity.

There is always huge fear, huge resistance, and then unfettered and profound joy when they nail it. I often take as my partner the largest or least physical comfortable person—I am not very big—in order to demonstrate that it will be okay. I will have the large young man do the pose with me where he ends up standing on my knees as we both lean back, his arm extended, like flying—because relationships are not about who is stronger, who is bigger, who has what qualities as an individual, but rather how those qualities can be used to find the balance, the center-point, the connected but turning planets, the tectonic forces of people. After this body work, we do an exercise where each person slowly and carefully touches the air about an inch from their partner’s body (with the back of their hand, not the front) in slow consciousness and respect. Then we do scene work.

There is always huge fear, huge resistance, and then unfettered and profound joy when they nail it. I often take as my partner the largest or least physical comfortable person—I am not very big—in order to demonstrate that it will be okay. I will have the large young man do the pose with me where he ends up standing on my knees as we both lean back, his arm extended, like flying—because relationships are not about who is stronger, who is bigger, who has what qualities as an individual, but rather how those qualities can be used to find the balance, the center-point, the connected but turning planets, the tectonic forces of people. After this body work, we do an exercise where each person slowly and carefully touches the air about an inch from their partner’s body (with the back of their hand, not the front) in slow consciousness and respect. Then we do scene work.

Although the process of inching teens towards intimacy, vulnerability, and co-stewardship is different when I teach Dramatic Improv (different exercises), the outcome is the same—surprise, elation, pride, bravery, and an enriched capacity for calm and courageous openness. It’s that trusting co-caring that relies on the relationship and not the self; it is intimacy. Inevitably the scene work is extraordinary, regardless if they ever met their scene partner before, regardless if their scene partner is someone they would even like under other circumstances.

Inevitably the performers carry forward a heightened awareness of other and interpersonal bonds, and the realization that they can create something truly incredible through this practice…onstage AND in life.

create something truly incredible through this practice…onstage AND in life.

Why was I surprised by my group of adults? Because for teens, the resistance grows of the newness of true co-caring and the terrifyingness of such intense vulnerability, and I had presumed that most people who do Stand-Up or joke-type comic improv would be focused on the self rather than the other. Yet in the workshop, they moved more quickly through the steps of deepening vulnerability and emotional intimacy than the teens. Why? Oftentimes, dealing with other targeted performance skills, adults are less willing to take risks than teens. I wonder if, perhaps, the value and impact of a vulnerable, co-stewarding practice was so great in their past (on stage? In real life? In actual relationships?) that they were able, in 50 minutes with people they had never met, practice the art of intimacy and create fabulously engaging Improvisation.

Regardless of the underlying reason, it was an incredible experience it was for me to work with them and have my assumptions turned upside down, and I will carry this learning forward with me to other times when I am teaching intimacy in performance practice—as something to be mindful of in the workshop participants’ relationships to the material and with each other—but also in my relationships with them.