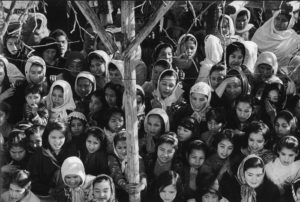

My Master’s Thesis was called “The Search for Indigenous Clown Forms in Afghanistan” (of course it was), stimulated in part by participation in a humanitarian mission to Afghanistan in February of 2002 with the the Italian military, an Italian film crew, and approximately two dozen clowns, mostly Italian. My passion for Silk Roads clowns continues unabated, and lately, people have been asking me more about them.

Thus, this blog entry! This is an excerpt (sadly made slightly ‘rumpled’ in tone in my attempt to cut words) from a paper I presented at a Silk Roads Conference in Australia. It also provides a working definition for clowning (which is really a social phenomenon, not a particular costume or make-up).

In any discussion of clowning, images of the court jesters of Europe and of Western antiquity prevail. Their presence in literature and common social construct is so profound that even in the United States (where, obviously, there have never been court jesters) they are as well known as the clowns of the Ringling Brothers, Barnum and Bailey Circus and the Cirque du Soleil. Jesters were long an integral part of Silk Road courts as well. Modern day aficionados of the form recognize the traditional importance of clowns in a court or a community; they are ‘the wise fools’, the touchstones of human nature, and those who reflect the weaknesses and strengths of a people. Clowns are not only a medium by which a community regains internal harmony and mutual caretaking, but also by which strengthens its identity and offers resistance in the face of external oppression.

There are traces of the clown forms from these regions that are pre-Islamic, detectable primarily through etymology and through current clown customs that have existed so long that they are described as heritage. Marcus Aurelius claims that the use of masks by the Greeks came from Central Asia, and indeed the word “Mask” comes from the Old Italian word “maschera” from the word “maskara” adopted into Arabic as a result of trade and invasion. “Mask” is also the word for the facial hide of an animal, particularly a goat or sheep. The tanned hide of a goat or sheep fits the human face well, as the eye sockets line up with our own and the outer contours are also approximately the same size. Such masks were worn in sacred rituals both serious and humorous throughout ancient Central Asia.

Vestiges of these customs remain in the goat horns that adorn some of the rural mountain Islamic shrines in Afghanistan, in the modern (as of the 1970s) traditions and celebrations in some regions of Pakistan, and in the legacy of masks or mask-like makeup by clowns in Bali, India, China, Japan, Russia, and Europe. (Of course, they are also the likely source of the western Christian notion of the devil as having horns and other goat features.) The Italian clown form commedia dell‘arte has a predominance of masked characters, and the oldest character, Arlecchino, has a lump on the right side of his forehead, which is said to be either a syphilis lump or a goat/devil horn. Finally, the clowns of Kashmir are called “maskara”, and their ‘make-up masks’ include red markings on the cheeks and a big red nose.

The exchange of styles, skills, characterizations and so forth was (and is) facilitated by the itinerant nature of performers. Three main reasons why performing clowns traveled were:

- The search for new markets

- As part of royal court retinue (they were expected to accompany various court members)

- Self-preservation; as laws changed and social pressure increased, it became in the clowns best interest to keep moving

To elaborate,

- The first factor was/is especially motivating for street performers: even if one is constantly developing new material, one cannot earn a living forever performing solely in one town.

- Clowns retained by the court traveled with the royal entourage on sojourns and even conquests, in addition to accompanying ambassadors or other court personnel on various journeys.

- The codification of Islam, the rising heat of debate between the learned as to the appropriateness of humor, and the widely varying enforcement of Muslim law to combat magic and other unnatural acts against God fueled the practice of roving. Magic and other acts against God sometimes included juggling, balancing tricks, acrobatics, slapstick, and unnervingly accurate mimicry.

In addition to providing impetus for a semi-nomadic lifestyle, the more strident legal measures also compelled many clowns to alter their performance style in order to protect themselves; to quote Gogol, “Even the man who is afraid of nothing is afraid of laughter.” These performers adapted the art of storytelling to create a “once removed” form of clowning, thereby protecting themselves without relinquishing social commentary. At this point many people wonder how storytelling can be clowning- are they storytellers or clowns? Acrobats, jugglers, storytellers, et cetera may also be clowns. They may clown in some moments and not in others. In the same vein, although many clowns wear masks or mask-like makeup, others do not. Moreover, the presence of makeup/mask does not mean that a performer is performing in a clown role. Clowning is a social phenomenon rather than an isolated incident or a set of prescribed actions. It is like a car- if I have a ‘race car’, am I automatically racing? No. I may be buying groceries. If I do not have a ‘race car’ am I never able to race? No. You and I could challenge each other verbally or non-verbally at a stoplight.

To provide context for understanding clown modalities, it is important to understand critical clown elements. For the purposes of this paper, we will use the following parameters to define ‘clowning’:

- There must be both a performer and an audience

- The performers and audience have an agreement; they enter willingly into a space-time in which different social rules apply, a sacred negotiation space

- The performer has a social status outside of the linear and vertical social strata

- The performer communicates a context of affection/caretaking of the audience/community

- The performance instigates awareness and/or change

The first four elements make possible the last, and without the impetus to awareness and/or change (and the awareness may be as subtle as the discovery of wonder), the performance cannot be thought of as clowning. It is the delightful but startling newness that compels this kind of laughter, opening the heart to momentary clarity and the possibility for transformation. In support, I share with you the writings of three great Islamic physicians:

‘Alî b. Rabban at-Tabarî: “Laughter is (the result of) the boiling of the natural blood (which happens) when a human being sees or hears something that diverts him and thus startles and moves him.”

‘Imrân: “Laughter is defined as the astonishment of the soul at observing something that it is not in a position to understand clearly (ta’ajjubu n-nafsi min shay’in lam yuqaddar lahâ dabtuhû) . . . The matter and gravitational force serving laughter is the pure, even-tempered blood that is distributed all over the body. Its end is the awareness of the soul, when laughing, of the meaning of laughter by gaining clarity about its purpose as either humorous or serious.”

Kindî: “Laughter —- An even-tempered purity of the blood of the heart together with an expansion of the soul to a point where is joy becomes visible.”

Without question, the personal discovery of the viewer is usually rooted in an altered social perspective, but it doesn’t need to be. Sometimes the clown is simply evoking awe and delight, reminding us that “There are more things in Heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy”. That there could be “more things in Heaven and earth” is at the crux of the debate in Islam as to whether or not magic, circus tricks, clown antics and so on ‘fly in the face of God’. Despite increased opposition at the beginning of the second Common Era millennium, there remained a faction that believed such performances were not the result of invoking the devil or false gods, but the revealing of the measure, beauty and wonder ‘of God’s capacity’.